Mythological Foundations of Spirited Away (part one)

Hayao Miyazaki's Oscar-winning movie Spirited Away is a perfect blend of the horrors of society and mythology from all over the world. Over the years, many have praised and discussed Spirited Away as a piece of art. Miyazaki is famous for skillfully blending myth and real life in his movies, and Spirited Away is no exception. Knowing more about the characters and the plot and the little details in the movie alongside the stories that inspired Spirited Away will eventually lead to a better understanding of it.

This blog is about my interpretation of some of the characters of Spirited Away and also some mythological motifs I happened to recognize. There are hints of different stories not only from Japanese culture but also from many other cultures around the world.

Torii Gates, Hokora & Dōsojin

|

| ©Studio Ghibli "Torii gate" |

Not long after the stone houses, Chihiro notices other roadside statues like the one in front of the tunnel's entrance. Other than signifying the realm of the gods, they represent boundaries. Chihiro's father is forced to hit the brakes of his car because of the stone statue in front of the tunnel. This is when the parents are interested in exploring further, but Chihiro gets cold feet and suggests they don't progress further and go back to the road. Another interesting point about Hokora is that they're said to protect travellers and people in transitional phases, as our protagonist, Chihiro's personality and views, will eventually go through a massive transformation.

Shadow Kami & Pigs

|

| ©Studio Ghibli "Yokai" |

As the sun sets, everything around Chihiro starts to change rapidly. She begins to feel even more nervous and runs around to find an exit as soon as possible after Haku warns her that her presence is forbidden in this place. The marketplace is filled with transparent, shadowy figures that frighten Chihiro. These figures represent kami, or gods that traditionally aren't visible to the human eye until they inhabit another form, like trees, rivers, and other elements in nature. In this movie, their depiction is close to yokai, or spirit, in Japanese folklore.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

Soon after that, Chihiro finally gets to find her parents, but, tragically enough, they've both been transformed into pigs. At first glance, the pigs appear to be a metaphor for Chihiro's parents' greed and gluttony or simply consumerism and how it can strip a person of their identity. Later in the movie, it's revealed that Yubaba, the owner of the bathhouse, has transformed them into pigs for eating the food of Kami without permission.

Eat food from this world to stay.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

Apart from Greek mythology, in the Japanese creation myth, the story of To the Underworld ("Yomi no Kuni") might also be another inspiration for this scene. Izanagi and Izanami are considered to be the creators of the Japanese archipelago and the immediate ancestors of many deities. In this specific story, Izanami, terribly burnt from childbirth, dies after giving birth to the Kami of fire. Her death is the first-ever death in Japanese mythology.

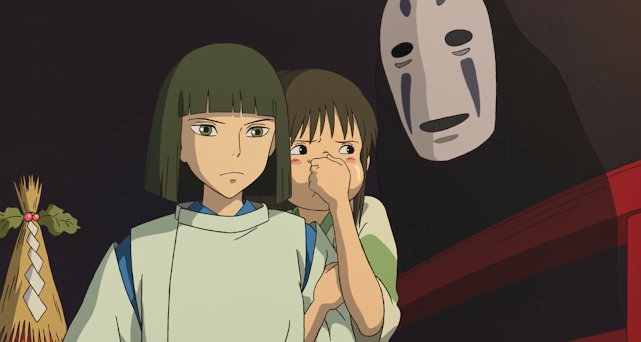

No-Face and other minor characters

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

The first time Chihiro encounters No-Face is on the bridge where she has to hold her breath to pass in order to not disturb any god or spirit. But No-Face is different from other Kami, and it shows from its first appearance. Chihiro attracts his attention even when she's not breathing, as we see No-Face turning his face and looking at Chihiro.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

Putting myth aside, on a personal note, I think No-Face mirrors what he sees around him. He isn't moved by Chihiro's kindness or Yubaba's greed. He starts to behave generously around the workers of the bathhouse because he's mirroring Chihiro's kindness and love in her heart (since we get to learn that Chihiro is in love with Haku and cares for him) and the workers' greed and self-interest once he's let in the bathhouse and starts to consume huge amounts of food. Towards the end of the story, he is pretty calm and creative in Zeniba's cottage and starts knitting because he's again mirroring Zeniba's lifestyle and views.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli "Namahage" |

There are so many minor characters in Spirited Away that have mythological backgrounds in the other world as more guests arrive at the bathhouse. The horned Kami resembles "Namahage," a Japanese folklore creature known as "Oni." They're horned, demon-like ogres with straw capes and Oni masks. In Akita prefecture, there's a yearly tradition in which men would dress up as Namahage to scare children into good behaviour.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli "Kasuga-Sama" |

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

The fact that we don't get to see any other creatures like Kamaji in the movie is that he's the last of his kind and has been enslaved by Yubaba's greed for money and capitalism in the bathhouse. Despite Tsuchigumo's demon-like nature and appearance, Kamaji happens to be very kind towards Chihiro as he helps her get a job and shelter herself, and later in the movie gives up his 40-year-old train tickets for her to save her parents.

|

| ©Studio Ghibli |

On a personal note, Spirited Away is definitely a movie that could move anybody of any age at any time of their life. It's one of those movies that always leaves one intrigued with a new perspective to take into consideration. Hope you enjoyed this analysis of Spirited Away. Come back for part two!

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment